3D Printing in Space: A Guide to Lunar and Orbital Additive Manufacturing

Extraterrestrial exploration has forever attracted human interests, and conquering space has been an ongoing goal since the previous century, now manifest in a space race ramping up between billionaires and their respective companies.

As we explored in a recent article about bioprinting in the movie Mickey 17, 3D printing has emerged in recent years as a significant asset for the space industry.

However, these recent developments are not without precedent. In 2014, a 3D printer was sent into space, marking the maiden voyage for applications in such extreme conditions. Since then, usage has seen an increase by astronomical proportions.

Lunar AM has evolved from small repairs and prototyping for weightlessness experiments to integration into rocket design. Moving forward, on-site manufacturing could be a very real possibility. 3D printing is already an industry leader for mobile production on Earth; why not a bit further afield?

In recent months, AMFG has covered emerging applications in AM, including portable defence, maritime, and construction– keeping abreast of the latest developments is crucial for a market so sensitive to technological innovation.

In today’s article, AMFG examines the reasons why additive manufacturing is being used in space, how it’s currently being leveraged, and the future possibilities for lunar additive manufacturing.

The story so far: From PLA tools to metal structures

The journey began in 2014 when NASA and Made In Space (now under the Redwire name) launched the first fused-deposition-modeling (FDM) printer to the ISS. Its flagship print: a simple but functional ratchet wrench, proving microgravity had no detrimental effect on the layer-by-layer plastic process.

Following this success, the Additive Manufacturing Facility (AMF) arrived on the ISS in 2016. Larger and more robust, built to run continuously with minimal astronaut intervention, AMF utilizes ABS, PEI/PC, and HDPE filaments to print mission-critical tools and components directly onboard.

Milestone prints are various, ranging from the first plastic wrench in June 2016 and a medical finger splint in June 2017, to the first piece of art printed in orbit in early 2017. To date, over 115 objects have been produced so far, underscoring AMF’s versatile, operational body of work.

Yet printing in microgravity necessitates engineering ingenuity.

Without convection, heat must be managed through active systems. Extrusion must be precise; filament must adhere without gravity. Enclosed environmental controls regulate temperature and humidity to ensure the material behaves predictably.

Maintenance and monitoring are handled remotely, with operators queueing jobs from the ground, while cameras in the rack provide status updates. Astronauts only fetch finished parts, reducing crew time and complexity.

Material advancements

Commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore holds up the first object made in space with additive manufacturing. Image courtesy of Made in Space[/caption]

This ingenuity is manifested in advancements in new materials and developed recycling capabilities.

For example, take PEI/PC, a durable aerospace-grade filament first used in 2017 which offers strong thermal and UV resistance and is suitable for structural applications and future EVA tools.

HDPE/GreenPE is a renewable, flexible polymer used for non-structural parts like irrigation fittings, and the Refabricator system converts waste into filament onboard– a step toward a circular economy in orbit.

A crucial element to AM sustainability (on this planet) is being able to additively manufacture parts close to where they will be used– we saw this in our article about portable AM for defence. In space, regolith printers like Redwire’s are able to test lunar dust as potential construction material for habitats. This demonstration successfully showed the ability to develop a permanent presence for humankind on the Moon using in-situ resources.

Yet the list of materials available is diversifying. In early 2024, the first metal 3D printer designed for microgravity launched to the ISS as part of ESA’s Metal3D initiative. Developed by Airbus, Cranfield University, AddUp, and Highftech, this compact, laser-based filament system successfully printed the first metal part in space by August 2024.

Metal printing in orbital manufacturing boasts several advantages. Components made from metal can handle loads that are plastically impossible for polymers, making them ideal for spacecraft repairs or load-bearing structures. This, combined with long-duration-flight capabilities, and the ability to diminish mission risk by manufacturing replacement parts without waiting for shipments, means that metal printing is destined for further use on future missions.

The material landscape for orbital manufacturing has evolved from plastic, to high-performance polymer, to metal. Efforts to implement IRSU (in-situ resource utilisation) will, if successful, use lunar or Martian regolith to produce metal or amalgamate feedstock for extraterrestrial construction.

In April 2025, researchers at the DSEL in China revealed a working prototype of a ‘lunar soil brick-making machine’. The system is designed to build infrastructure directly on the Moon, focusing solar energy to melt lunar soil, or regolith, and mold it into usable bricks through a solar-powered 3D printing process.

The next step for out-of-orbit material manufacturing is food (even astronauts need to eat). The further away from Earth, the more a large food supply is needed. Astronauts have to carry large stocks of food, which occupies much space and weight.

In 2013, NASA announced funding for the 3D printer development that could create food for the astronauts, cooking ingredients stored in powder form in special cartridges. The printer would mix the cartridge contents, add water or oil, and produce various dishes. The first dish available was pizza, printed layer by layer. The cartridge will last for 30 years of operation, meaning it can be used at first on the ISS, but also can be employed on the Moon or Mars in the future. Astronauts can have more flexibility according to food preferences and allergies, and will be able to maximise the nutritional value of their meals.

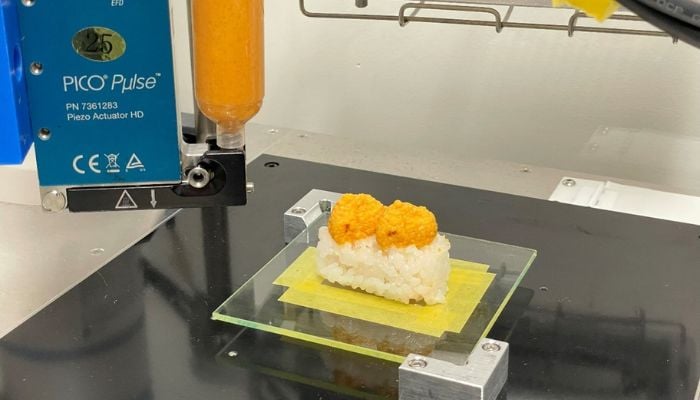

For the consumer after a healthier option, engineers at IHI Aerospace and Yamagata University have begun to develop 3D printed sushi that they hope will be served to space tourists as they circle the planet in low Earth orbit. Space tourism has the potential to blossom in the near future, and 3D printing could be a crucial component, both in manufacturing and food production.

3D printed sushi immediately after production. Image courtesy of Nordson EFD

The benefits of 3D printing for lunar manufacturing

Optimisation of parts

Trips to space require a tight control of the weight contained on board. The lighter the rocket or satellite, the cheaper and more efficient the launch, as lightening the craft can reduce the amount of fuel needed and free up space to carry more useful equipment– each kilo saved is $10k less to launch.

Through DfAM, and particularly topology optimisation, 3D printing facilitates the creation of strong, complex shapes impossible to obtain with traditional methods.

As an example, 3Dnatives identifies cooling ducts used in rocket engines, which evacuate the intense heat around the combustion chamber. With 3D printing, these can be directly integrated into the parts, which is very difficult, if not impossible, with traditional machining or injection moulding due to high costs.

Venus Aerospace, a company specialising in hypersonic propulsion, will incorporate a nozzle into its next ground-based demonstration that will be able to operate across multiple flight regimes without engine switching. This will allow vehicles to accelerate from takeoff to speeds exceeding Mach 5 with a single system, a game-changer for hypersonic travel.

New materials

The demands on materials in the space industry are high; extreme temperatures, variations in pressure, thermal shocks, radiation– the list goes on. As we’ve explored above, 3D printing in space is able to benefit from a litany of advanced materials.

These include metal alloys such as titanium, aluminium, and Inconel, well-known for their properties of lightness and thermal resistance. Fibre-reinforced composites additionally offer strength and flexibility.

For example, 3D Systems’ Application Innovation Group is collaborating with various universities to produce high-performance radiators and heat pipers made from titanium and nickel-titanium alloys. By embedding heat pipes and shape-memory alloy components directly into radiators through 3D printing, the team is addressing the weight and manufacturing complexity of traditional thermal systems, making future space missions more cost-effective and capable.

The ISS has already printed optical fibers with fewer defects than Earth-bound versions. ZBLAN is a glass alloy made of zirconium, barium, lanthanum, sodium, and aluminium fluorides, each with different densities and crystallisation temperatures. The increased efficiency of ZBLAN could translate into significant energy savings by reducing the need to boost the signal on long-distance transmissions.

In terms of printing processes, DED, LPBF, DMLF, and extrusion printing techniques shape these strong, flexible materials into complex, precise and optimised parts.

Assembly made easy and cheap

Much like 3D printing when used in other applications, the simplification of processes and reduction of costs is a big factor when deciding which manufacturing technique to use.

3D printing also makes it possible to avoid assembling thousands of parts. SAB Aerospace recently printed a one-piece rocket nozzle, which typically requires the assembly of thousands of parts. Elsewhere, Relativity Space has greatly simplified the construction of its Terran rocket by reducing the number of components by 1000.

Printing in orbit may revolutionise how space travel is conducted. Photocentric has unveiled a high-speed 3D printer designed to manufacture components directly in orbit, permitting astronauts a new level of self-sufficiency. The CosmicMaker can operate in microgravity, turning liquid resin into solid parts using light.

Manufacturing in microgravity

3D printing is a technology unique in orbital manufacturing. Astronauts can additively manufacture objects directly in space, which greatly reduces dependence on expeditions from Earth, which are frequently excessively long and costly.

The wait for spare parts reduces from a matter of weeks and months, to mere minutes and hours on board. This vastly improves the safety and efficiency of missions, limiting interruptions significantly and increasing operational resilience.

The On Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing (OSAM-2) mission, whilst seemingly completed without a demonstration, aimed to construct large, self-assembling architectures that cannot currently be stowed and launched from Earth. The plan was to construct two 3D printed truss structure beams, only 10 metres in length but with the potential to expand to a 100-metre scale.

While a demonstration never took place, the fact that these processes are being developed is an exciting step toward space architecture. 2024 saw the first metal part manufactured directly on board the ISS, showing that the technology works under space conditions, even if still in the trial phase.

Big benefits for astronauts

Long-duration space missions mean that it isn’t always possible to carry all the medical equipment required. But thanks to 3D printing, astronauts can manufacture useful objects on site to treat injuries or certain health problems.

As we covered in our article on portable AM for defence, 3D printing facilitates the production of splints or surgical tools on site, meaning that potential gaps in the supply chain don’t put team members at risk.

Bioprinting in space is advancing, too. A human meniscus has been successfully bioprinted on the ISS using the BioFabrication Facility. On the ground, bioprinting soft tissues is difficult, and requires scaffolding to prevent the printed tissues from collapsing under gravity.

But, in space, no gravity=no problem. The hope is not only that 3D bioprinting can be leveraged in space for astronauts, but could also be used to print organs in space and then sent down to Earth for usage.

Case study: Success in 'vomit comet'

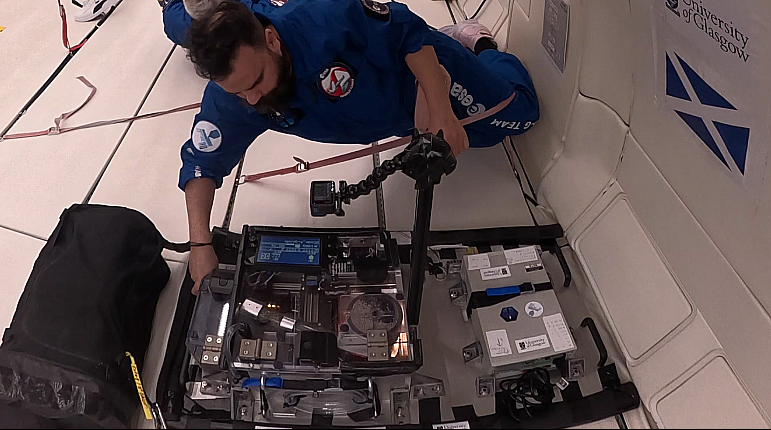

A researcher evaluating 3D printing system in a microgravity simulation aboard a parabolic flight. Photo via University of Glasgow.

Researchers from the University of Glasgow’s James Watt School of Engineering were successful in testing a 3D printing system designed to work in the microgravity of space.

The demonstration took place on the European Space Agency’s parabolic flight campaign, lovingly nicknamed the ‘Vomit Comet’. 90 moments of 22-second intervals of microgravity were used to evaluate the system, which uses a granular feedstock material in place of conventional filaments. The material flows reliably from the printer’s tank to the nozzle, even in the microgravity and vacuum conditions of space.

The event is a remarkable development in 3D application in aerospace; instead of sending items into space, risking destruction and damage when going into the Earth’s orbit, AM fabricators could be placed in space to build structures on demand. 3D printing in space has never been conducted in space outside the pressurised modules of the ISS, yet this demonstration indicates a system that could function perfectly in microgravity.

This approach could revolutionise the design and functionality of in-space equipment, with gear that remains in space for its entire existence, never reentering orbit or launching from Earth.

The next step is an attempt to secure funding for an in-space demonstration of the technology.

Final thoughts: Where are we heading?

Lunar AM is in a good space.

Companies like Made In Space, Redwire, Relativity Space, Airbus, and Cranfield are leading the charge, creating markets for space‑qualified AM tools and feedstock. Collaborations from the ISS, ESA, NASA, and UK investors are accelerating capability, and the potential for a serious lunar AM market is significant.

In terms of the tech, AMF has shown how to reliably print plastic tools; Metal3D is proving metal structures are viable in orbit; recycling systems are edging closer to autonomous sustainability; and regolith tests signal self-sufficient extraterrestrial habitats.

In the future, we could see AM parts on rockets, 3D printers on board for astronauts’ needs, and even entire buildings printed on the Moon (solar towers and more!).

At AMFG, we see a broader lesson: additive manufacturing is reshaping global supply chains, from local factories to orbital depots. Orbital manufacturing offers platforms for experimentation—manufacturing fiber optics, tissues, electronics—that could well spin back into Earth industries. And once we crack regolith-based printing, the mass manufacturing of habitats on the Moon and Mars shifts from speculative to feasible.

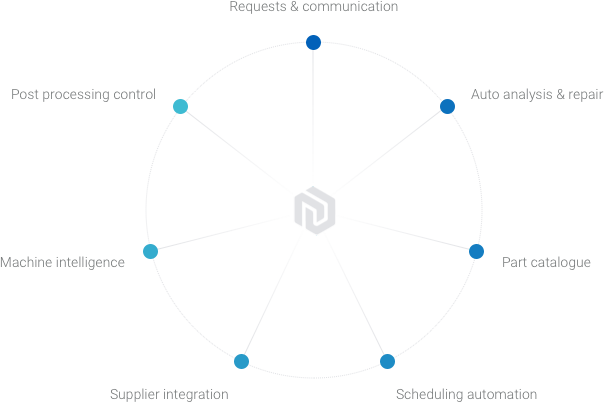

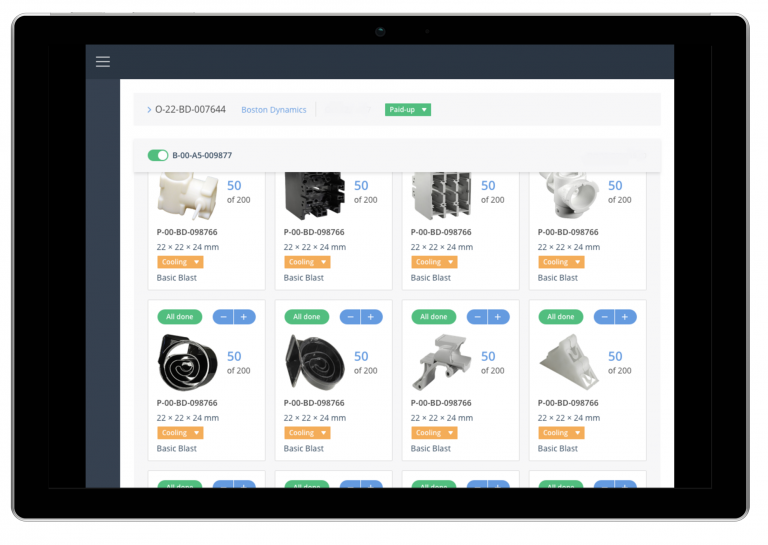

AMFG empowers high-mix, low volume manufacturers across industries, including aerospace, streamlining their operations with our cutting-edge software platform. Our scalable tools automate all stages of manufacturing operations, providing automatic quoting and order management, with 500+ integrations. Using our software, our clients can adapt to complex demand with efficiency and precision, securing their place at the forefront of the manufacturing industry.

Find out more here: Book a demo

.svg)